Dans son étude, Protzen étudie 2 carrières :

- Cuzco - Carrière de Rumiqolqa

- Ollantaytambo - Carrière de Cachiqata

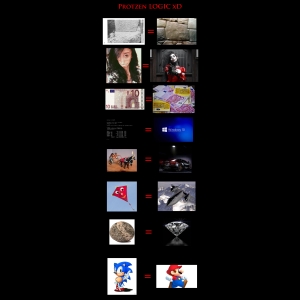

A Rumiqolqa, il dis avoir trouvé une zone encore vierge datant de l'époque des Incas : Llama Pit, ou l'on peut y voir des blocs finie sur 5 faces à tous les stades de leur fabrication :

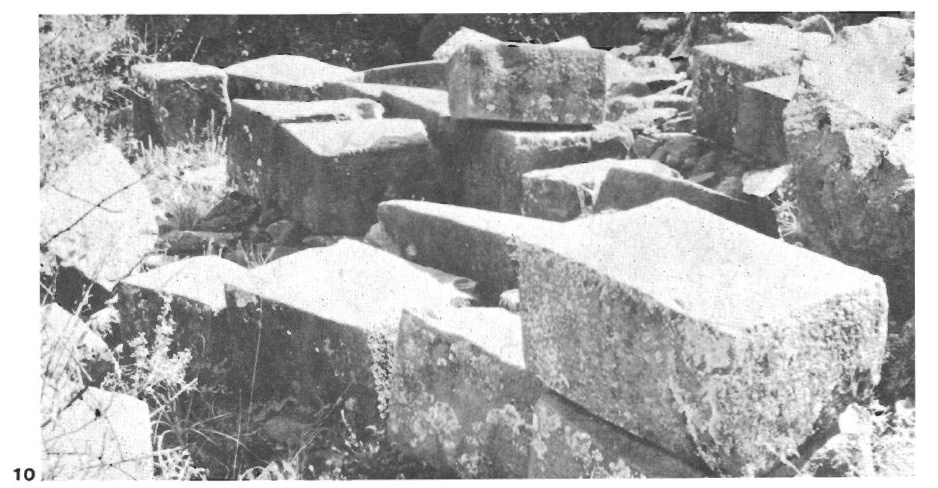

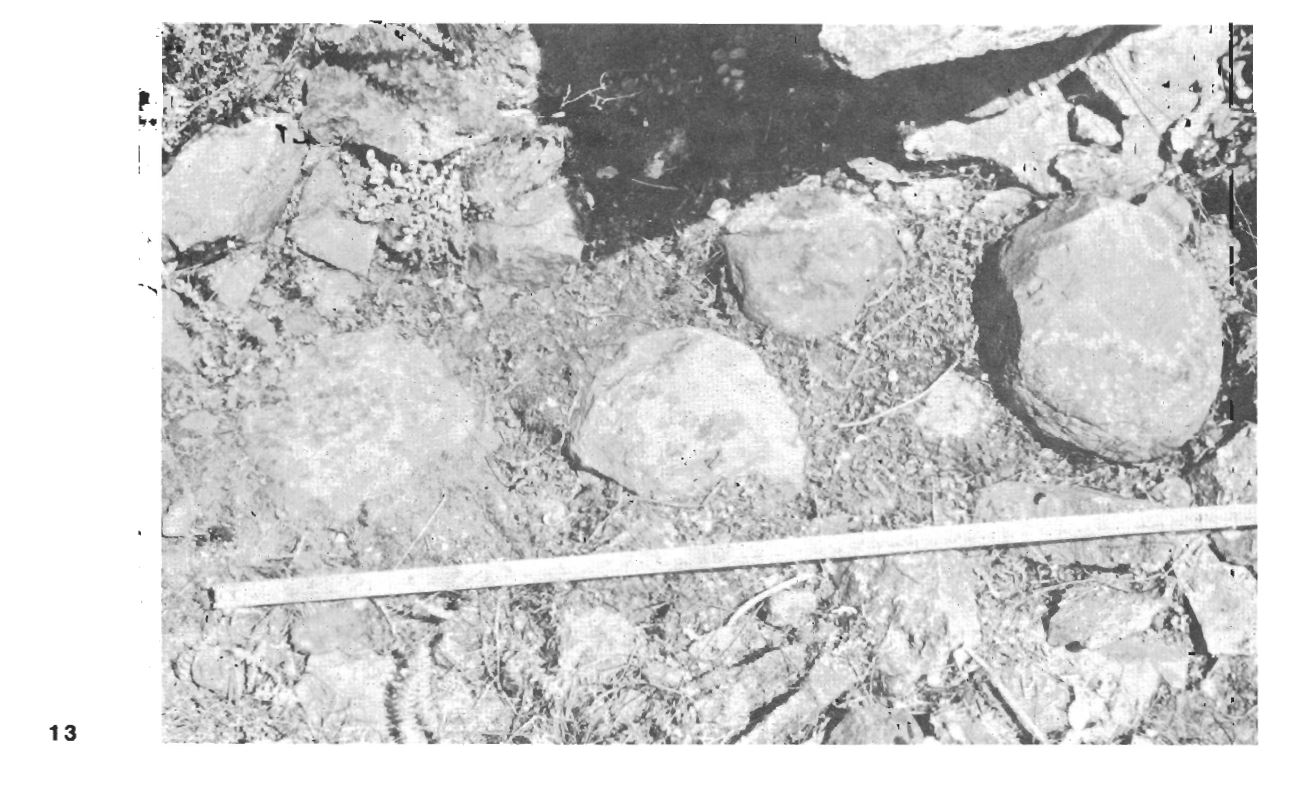

Protzen dis avoir trouvé de nombreux galets de rivières servant de marteau, et est donc certain que les Blocs en double courbure en Andésite ont été taillé avec.

Marteaux

Les marteaux retrouvés sont des boules de grès feldspathique en majorité, et aussi de quartzite, granite et de basalte d'olivine. Tous de dureté 5.5 minimum sur Mohs. Leurs poids peut allez jusqu'à 8Kg.

Bloc martelé :

Technique utilisant différentes tailles de marteau :

Expérience : Bloc d'Andésite

Après avoir observé le site de Llama Pit, et émis des hypothèses sur la fabrication des blocs d'andésite, Protzen tente une expérience afin de vérifier sa théorie. Il prend un Bloc d'andésite de 25*25*30cm :

Puis utilise un marteau de grès de 4kg pour faire une face :

Il frappe avec un angle pour créer une force latéral de cisaillement et briser le bloc en morceaux. Passez d'un bloc brut à une face dressé lui prend 20 minutes. Il dessine les bord avec un marteau d'environ 560gr.

Réaliser 3 faces et 5 bords lui prend 90min :

Bords arrondies

Protzen ici mesure des rayons en donnant des angles, chose impossible. Il commet ici une grosse erreur technique, on mesure les "Chanfreins" en mécanique avec des angles, et les rayons avec un rapporteur d'angle. Nous ignorons donc cette section sans intérêt.

Marques de surfaces

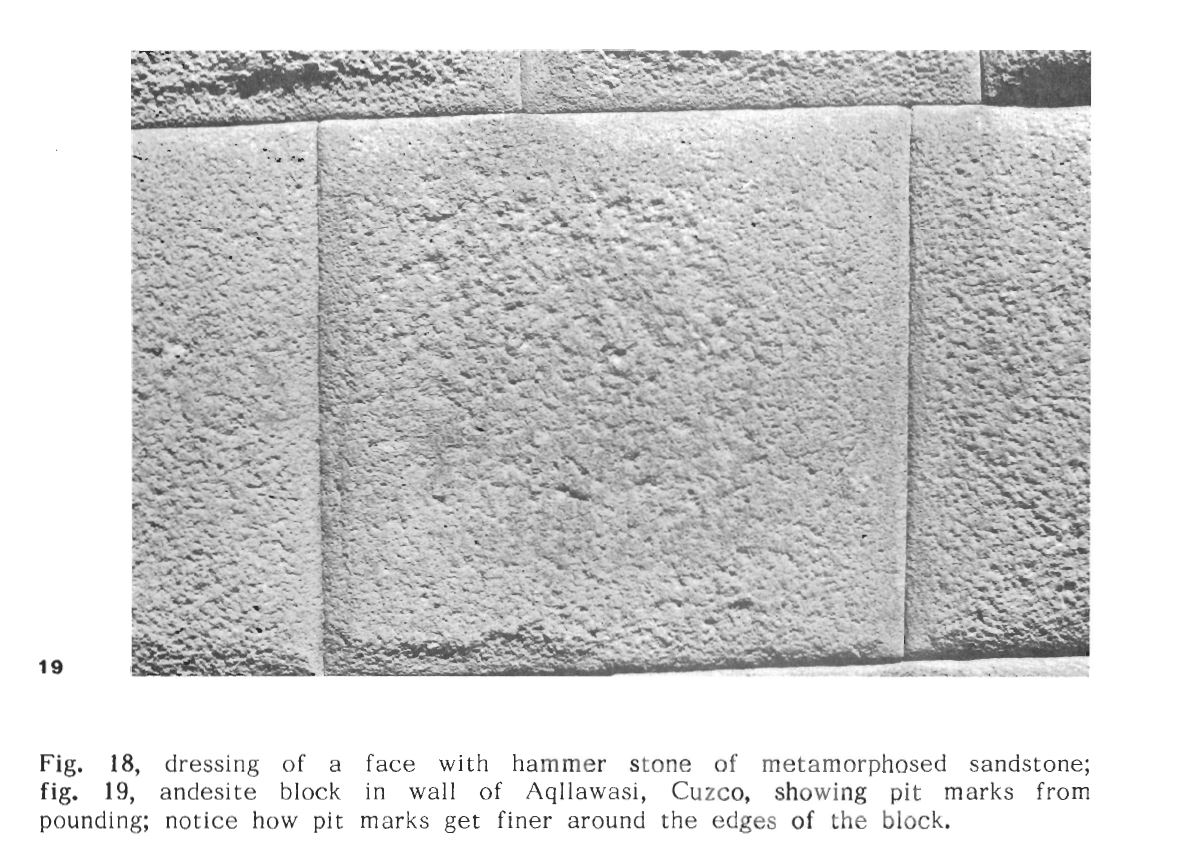

Protzen conclu que ses marques obtenues sont similaires à tous les Blocs Mégalithique :

L'observation de nombreux Blocs Mégalithiques permet difficilement de faire une généralité sur la technique employé, les états de surfaces sont très variables :

La conclusion de Protzen semble hâtif. Il semble également peut se soucier des Ergos visible partout ...

Protzen indique que sur certains blocs en calcaires on peut y voire des traces d'impact de marteau (figure 19) :

A notre connaissance, il n'existe pas et il n'y à pas de blocs en calcaires Mégalithiques en double courbure, alors pourquoi d'un coup Protzen parle-t-il de calcaire de dureté 3? Protzen semble s'égarer...

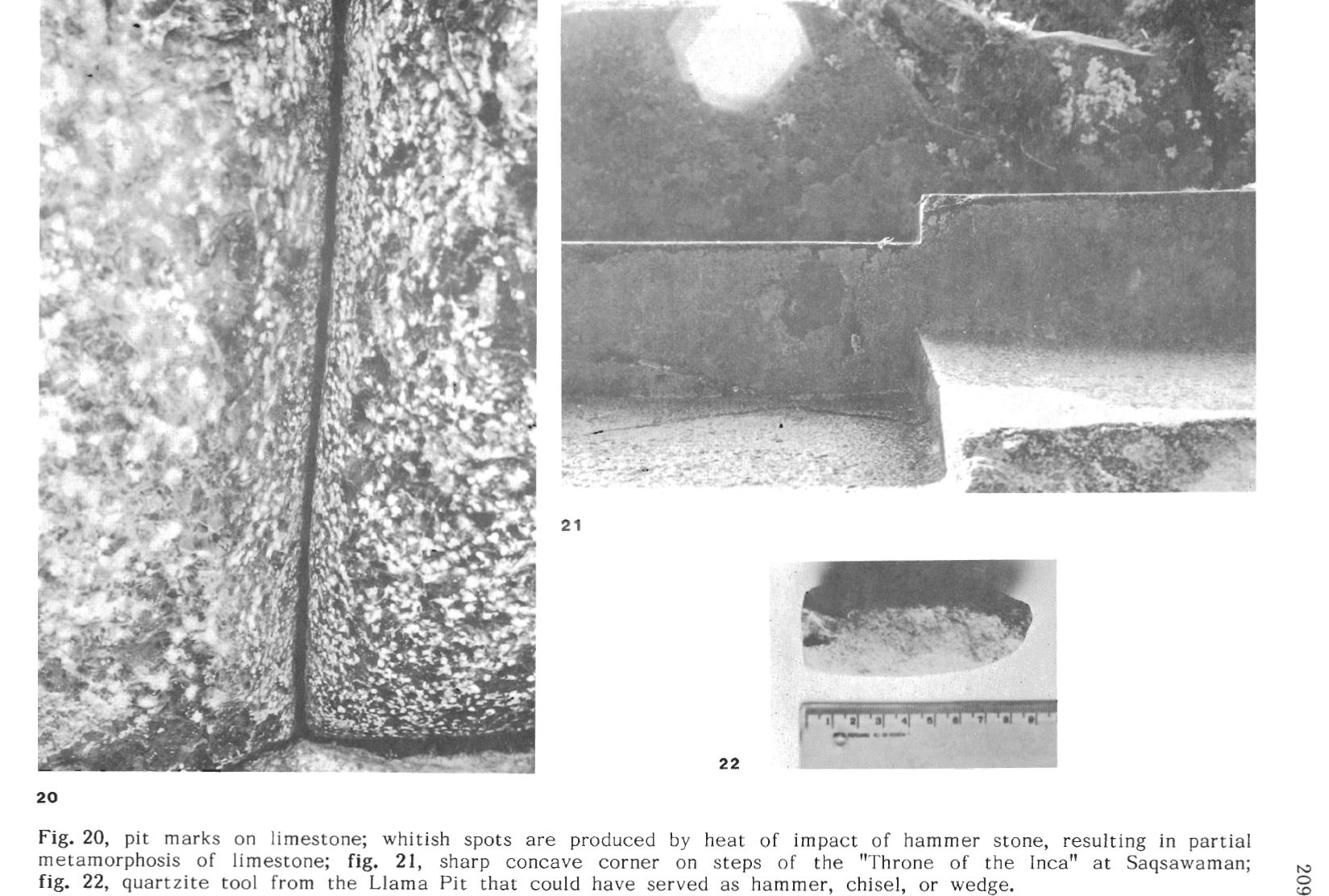

Bord saillant et doute

Protzen émet un doute sur sa théorie : à savoir que les bord tranchants sont impossible à réaliser en tapant sur la roche. Il trouve un outils en quartzite (figure 22) et émet l'hypothèse que cet outil est servie pour réaliser les bords tranchants. Mais Protzen ne fait aucun test, taper sur la roche et la briser, tous le monde l'a vérifier et peut en faire la démonstration, ce qui nous intéresse est la finitions précise et les bords tranchant, et Protzen n'en fait aucune démonstration. A ce stade nous émettons de gros doute sur son étude, qui est peu sérieuse.

Protzen, ayant bien visiter le site au vu de ses cartes, oublie (volontairement?) de parlez des Mini-blocs.

Protzen semble oublié des informations et orienté son études sur ses théories, ce qui est non neutre et anti-scientifique.

Trous

Protzen suggère que les trous ont été martelé puisque les 2 cotés sont conique. Nous n'aurons aucune démonstration encore de ce qu'il avance... Il suggère qu'un seul trou qu'il à vu pourrait être réalisé avec une tige de bambou et du sable en abrasif.

Comme la démontré Stocks, il est plutôt fort probable que tous les trous ont été abrasé avec du sable et un cylindre en cuivre.

Encore une fois Protzen fait passer SA théorie en premier, jusqu'à négliger la solution qui est juste.

Polissage

Although there is no doubt that the technique of pounding was the predominant method of dressing stone, there is evidence in the area I have investigated that the Inca stonemasons had knowledge of other techniques to work stone. Many of the building blocks at Ollantaytambo exhibit highly polished edges, while the faces show the familiar pit mark. This polish may have been achieved with bars of pumice, of which I found a few fragments.

Protzen est totalement convaincu et pour lui il n'y à aucun doute que tous les mégalithes sont fait par martelage. Il émet tous de même l'hypothèse que d'autre techniques puissent avoir été utilisé, notamment le polissage avec de la pierre ponce pour les bords. Encore une fois 0 essaie, alors que cela lui aurait été très facile à réaliser.

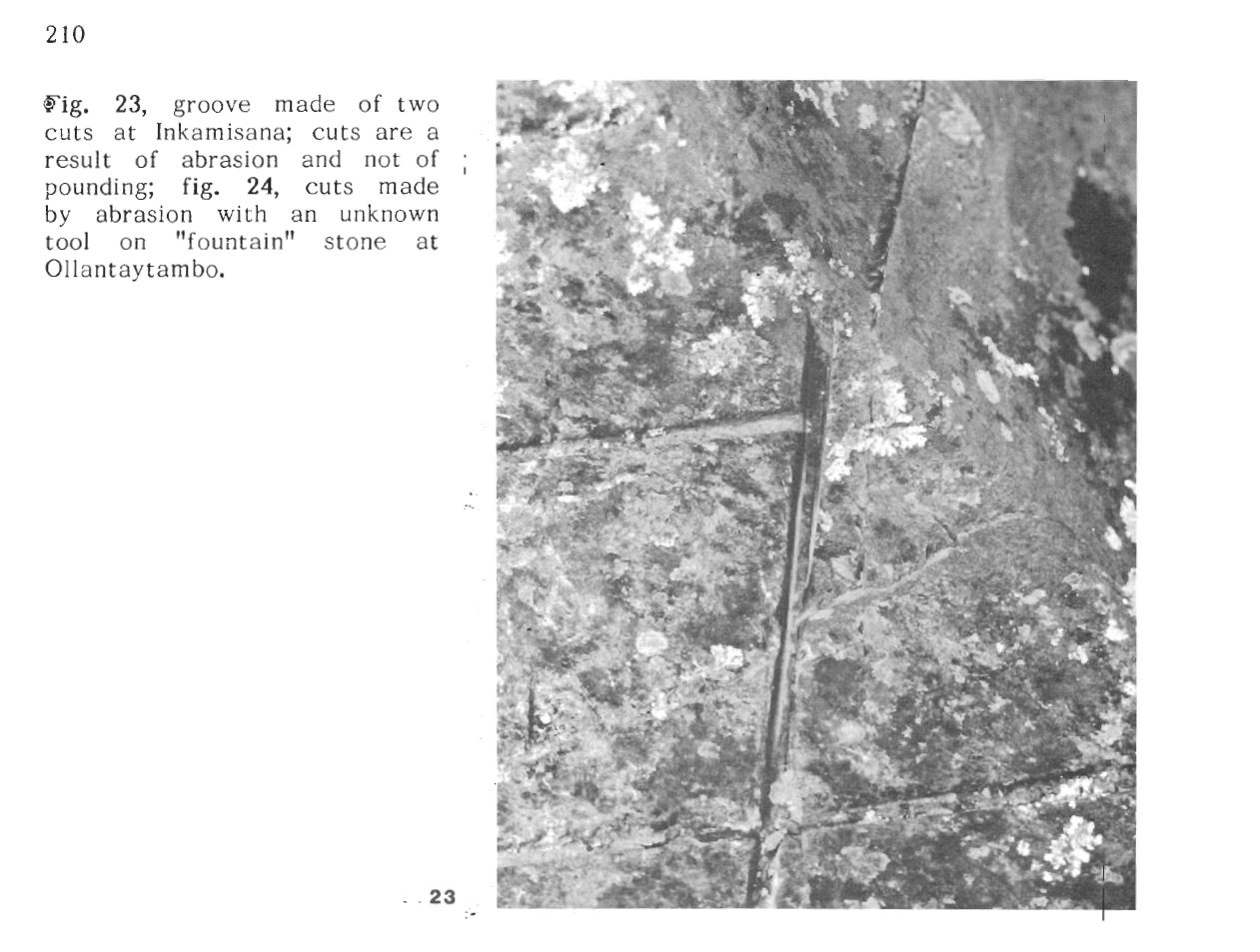

Abrasion

Protzen émet enfin l'hypothèse que l'abrasion à été utiliser, notamment sur un dallage à Inkamisana (Ollantaytambo) avec une Scie ou Lime :

Sur une fontaine à Ollantaytambo les traces sur un bloc lui font suggérer une scie :

Il avoue n'avoir aucune idée des outils utilisé pour réalisé ce genre de coupe :

But again, the cuts could not have been made with a string or wire, the curvature of the eut is contrary to what one would obtain with a string. There is more evidence throughout the territory that I have explored to show that the Incas did on occasion saw into stones. What tools they used for this I do not know.

Joints

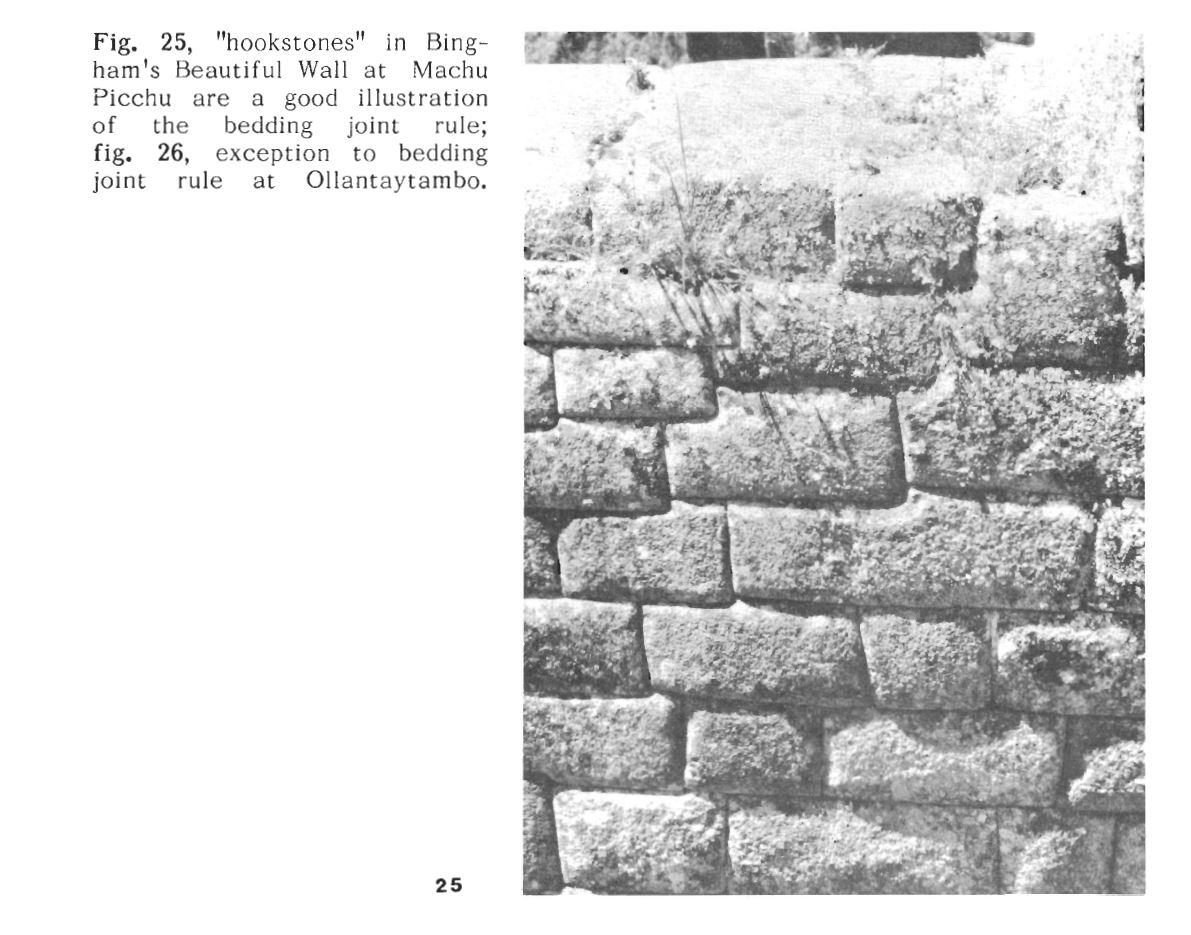

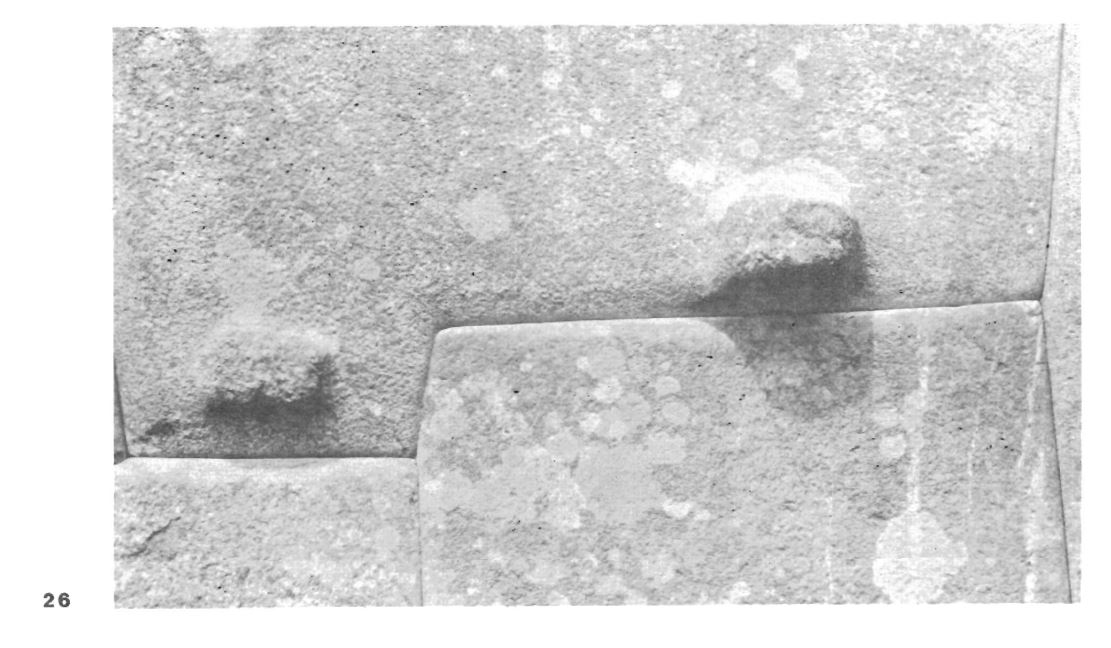

Nous ne comprenons strictement rien de ce que Protzen à voulue nous dire dans son chapitre "Bedding joints". Il parle d'une règle général :

The bedding joint of each new course is cut into the top face of the course already laid below it.

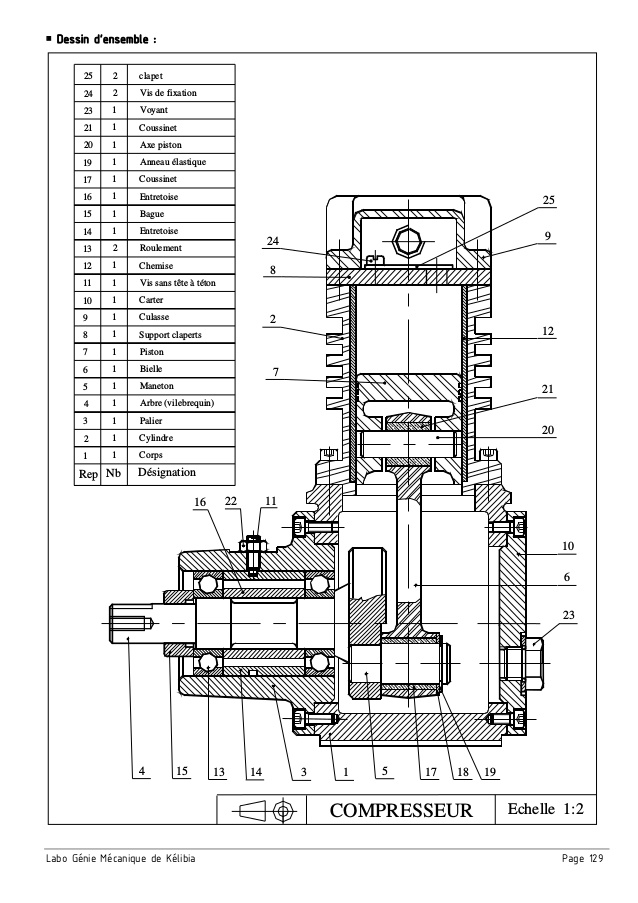

Il montre un shéma :

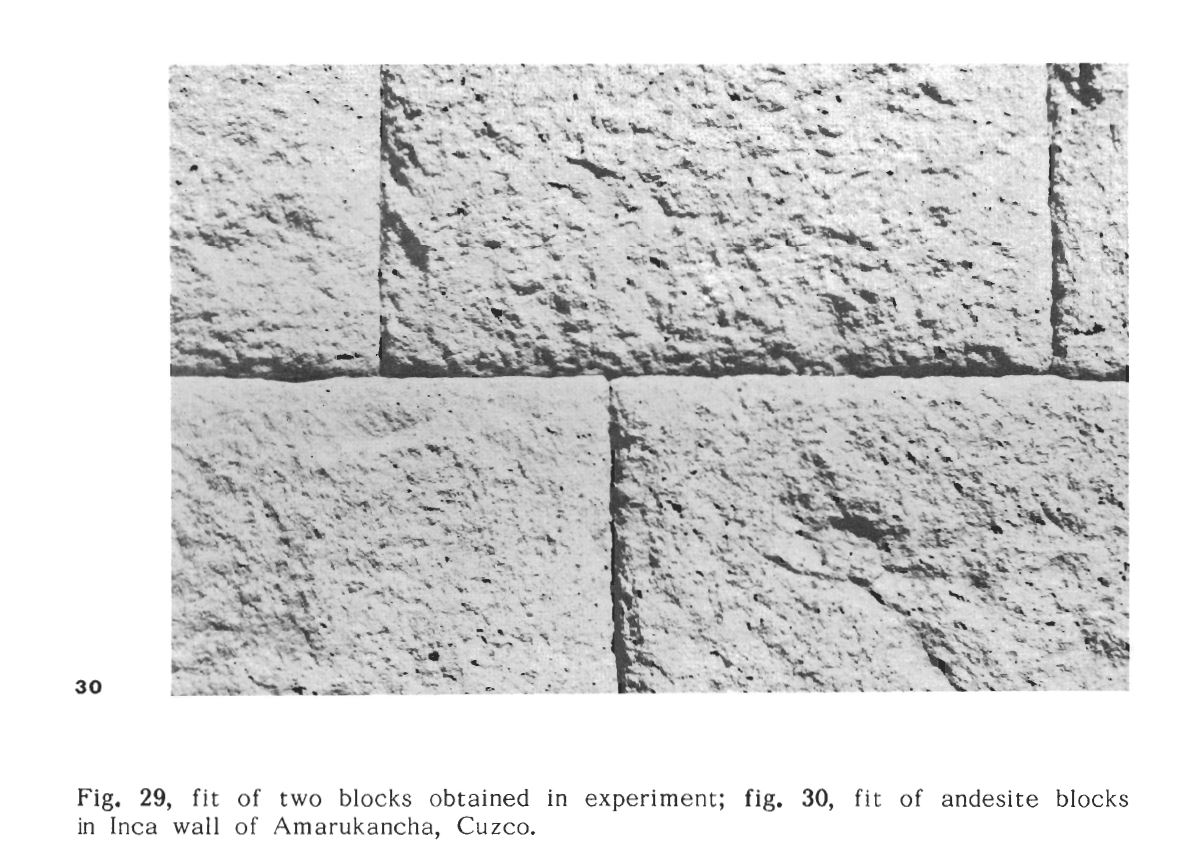

Montre un mur Incas pour appuyé sa règle général :

Mais sa règle général n'est en faite pas toujours valable :

Réfutation de Ravines

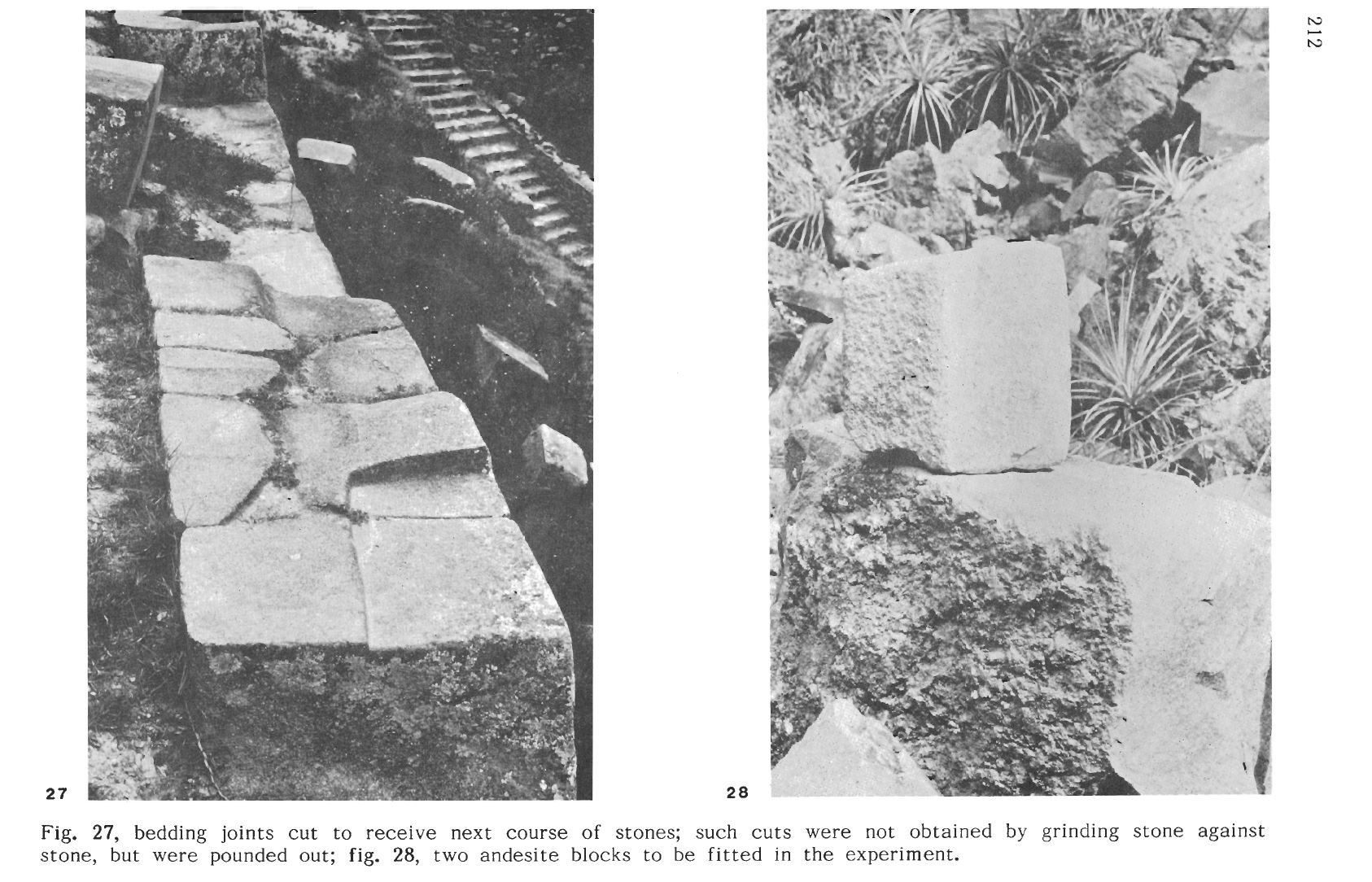

Protzen réfute l'idée que les blocs ont été frotté les uns contre les autres comme le suggère Ravines en 1978. (Figuze 27).

Poursuite de l'Expérience

Protzen continue son expérience pour vérifier ses Hypothèses en prenant un Bloc d'andésite plus grand que le premier, afin de réaliser un joint entre les deux (Figure 28). Il ajuste la face du petit bloc par martelage.

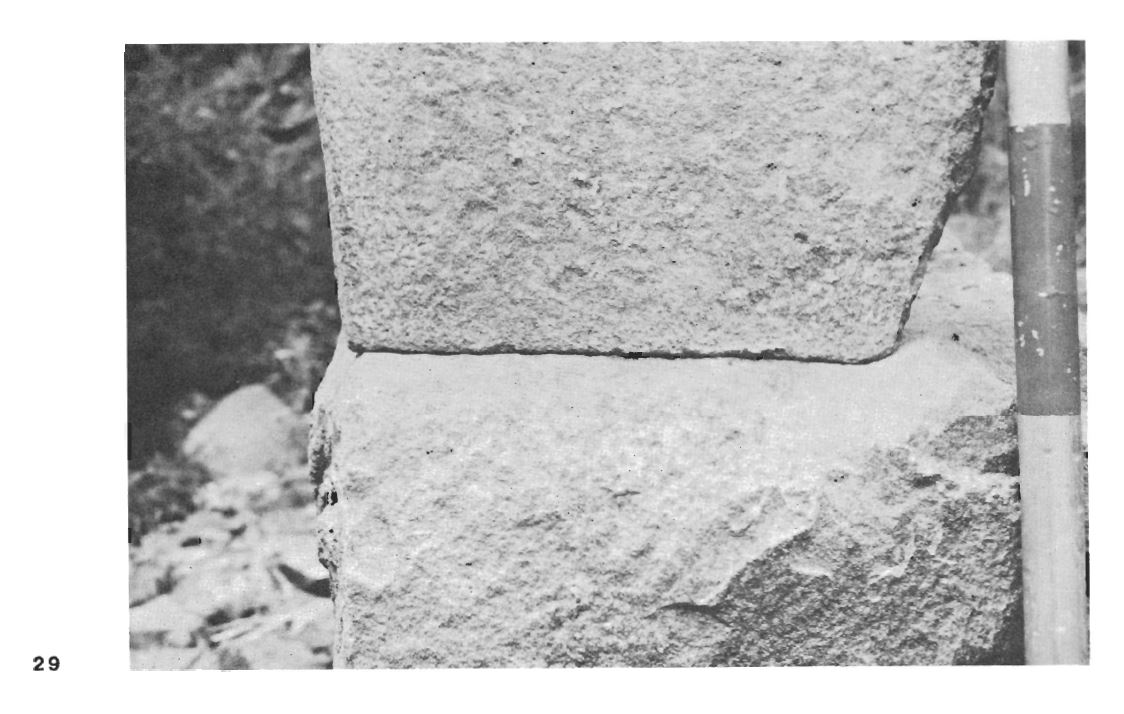

Voilà ce qu'il obtient :

Protzen nous dis :

The technique for fitting two stones is thus one of trial and error. I concede that this technique appears to be tedious and laborious, especially if one thinks of the cyclopean blacks at Saqsawaman or Ollantaytambo. It should be remembered, however, that to the Incas time and labor were probably of little concern, and my experiments show that with some practice one develops a very keen eye for matching surfaces, so that the number of trials can be reduced considerably. The suggested method works, and it has the advantage of not postulating the use of tools and other implements of which no traces have been found.

En gros les Incas procédais par essaies/erreurs, Protzen est ici totalement hors réalité du métier de la mécanique et des ajustements précis, ce n'est tous simplement pas son métier, il aurait du consulter des Ingénieurs avant de faire de pareil conclusion qui frôle le gag.

Note sur la précision

Je travail en Bureau d'étude depuis plus de 12ans en Automobile, Aéronautique, et je conçoit des pièces de haute précision en double courbure en usinage, la seul solution est d'utiliser des machines à commande numérique, ce qui coute très chère, car la main de l'homme ne peut réaliser ce genre de chose précis au centième. Si l'homme était capable de produire des blocs à 14 faces en double courbure de dureté 7 précis au centième, j'aurai déjà monté ma société et fait couler à moi tous seul toutes les grandes industries au monde.

Bref les Incas n'était pas des hommes, mais des Dieux meilleure que toute nos Machines Numérique moderne en terme de précisions. (Voir Tolérances générales).

Poursuite de l'Expérience

Protzen appuie sa théorie de "Essaies/Erreurs" à coup de martelage avec José de Acosta wrote in 1589 :

And what one most admires is that, although these [ stones] in the wall I am talking about are not eut straight but are very uneven in size and shape among themselves, they fit together with incredible precision without mortar. Ali this was done with much manpower and much endurance in the work, for in order to fit one stone to another so precisely it was necessary to try the fit many times, the stones not being even or full.

C'est assez triste qu'il doive presque retourner au moyen-Age pour justifier sa théorie, qu'aucun Ingénieurs actuel n'a confirmer, étant chose impossible.

Critique du résultat obtenue

Protzen semble satisfait de son test, nous pensons plutôt que c'est un échec total. Toute l'étude porte sur des blocs en double courbure de dureté 7, et Protzen réalise seulement un joint droit sans aucune profondeur, chose que l'on sait réalisable facilement depuis toujours. Protzen fait ici des conclusions hâtives non scientifique. La réalisation d'une simple courbure en U aurait déjà démontré l'impossibilité de la tâche. Cet expérience est un échec comme la Pyramide de NOVA.

Un archéologue n'est pas un Ingénieur mécanique, et ne devrais pas exécuter ce genre d'expérience sans aide, cette étude est à jeter entièrement, et d'une incompétence sans nom. Les Pyramidiots et dérives naissent suite à ce genre d'étude.

Ultime Théorie Extra-ordinaire de Protzen

Protzen aurait dû s'arrêter là, il n'a clairement aucune idée de comment sont fait les blocs et son test ne démontre rien. Il nous dis :

The technique for fitting lateral joints I assume to be similar to that used

for the bedding joints:

"The new block to be laid is fitted into, and the joint cut out of,

the lateral block or blocks already in place."

Puis nous montre ceci :

Protzen croit-il en ce qu'il dis?

-A-t-il penser que les doubles courbures empêche dans la majorité des cas d'enlever les blocs par l'avant?

-La majorité des blocs dispose d'angle vif qui casserait vite si on l'enlevai des milliers et milliers de fois.

-Et? Comment il ajustai un bloc enlevé sur plusieurs faces?

Il est plutôt probable qu'il voulait se faire bien voir du milieux archéologique, et donc pour des raisons de gloire, il à tenté de faire passer ses théories totalement fausses et impossible à reproduire pour des théories officiels si on pourrait dire, et cela à fonctionner, nous lisons beaucoup d'articles citant Protzen dès qu'on parle de fabrication lié aux Mégalithes.

Protzen sans limite...

Protzen va encore continuer dans ses théories folles et va allez cette fois encore plus loin.

Comme mentionné plusieurs fois, les blocs sont assemblés en double courbure, et une étude qui ferai grandement avancé les choses serait de scanner tous un mûr, afin de modéliser les courbure exact, et ainsi émettre des hypothèse quand à l'ordre d'assemblage et technique de fabrication. Malheureusement, en 2020, nous ne disposons pas d'un telle rapport.

Mais attention Protzen équipé d'un cahier et stylo va nous faire un rapport sur l'orientation des double courbure, totalement invisible puisque les blocs sont coller entre eux. Souvenez vous du Shéma 3:

Il dis avoir inspecter les plans de jonctions. Et? Est-ce une mauvaise blague de Protzen? Que peut-on faire de 2 lignes? Il est impossible de mesuré des double courbure 3D invisible à l'oeil sur un shéma 2D, Protzen joue à l'Ingénieur Mécanique avec un niveau collégien... Plus je lis cette étude plus j'ai l'impression qu'il se moque royalement de nous.

Il part ensuite dans une théorie de clé de voute qu'on mettrai à la fin, Protzen voit apparemment à travers les murs et est doté de super pouvoirs.

Page 13 Protzen avoue que son Hypothèse de montage et de clé de voute n'est pas sur, qu'il n'a pas analysé suffisamment de murs et qu'il était limiter en profondeur sur 5cm max (ah bon?). Me voilà grandement soulager, j'ai vraiment cru avoir à faire à un idiot finie. Il avoue que ses plans sont totalement faux, puisque les doubles courbures peuvent partir dans toutes les directions en interne. Mais alors pourquoi prendre de telle mesures inutiles?

Transport

Pour le transport il ne l'aborde pas car ce n'est pas le sujet de l'étude :

The problem of laying sequences leads me to a set of questions regarding the handling and transportation of the stones, a subject that I have not taken up yet, not because I find it uninteresting or unimportant, but simply because I have neglected it in favor of the issues addressed here.

Conclusion

Un des problèmes qui ressort de l'Archéologie actuel est le manque d'étude sérieuse, et le manque de dialogue avec des Ingénieurs Civiles, mécaniques. Les Archéologues utilise principalement 2 études pour baser toutes leur hypothèses, qui sont anciennes et fausses (celle de Protzen et Trilithon de Baalbek : Jean-Pierre Adam).

Son étude est orienté et non neutre, nous encourageons les Archéologues à ne plus se baser sur ce genre d'études. Nous insistons bien sur ce points :

Actuellement, aucune étude, aucun test et aucune théorie ont démontré la fabrications de blocs en dureté 7 en double courbure avec des précisions au dixièmes voir centièmes. La main de l'homme est totalement inadapté, c'est pour cela qu'on utilise des machines très chère à Commandes Numériques.

Les Archéologues se basent sur des travaux faux et ignorent tous les points qu'ils ne comprennent pas par manque de connaissances, un Archéologue n'est ni un Ingénieur Mécanique ni un Ingénieur Civile, et les Chercheurs de vérités se sont braqué ce qui les fais passez pour des Pyramidiots en partant dans toutes les directions sans aucune connaissance historique ou mécanique. Il faudrait un juste milieux et rétablir le dialogue.

Nous ne rendons absolument pas honneur à notre passé, c'est une honte pour l'archéologie de s'appuyé sur des études faîtes à la vas-vite par des gens totalement incompétent sur les sujets traités. Les Pyramidiots ont encore de beau jour suite à la stupidité de telles études.

Sources - Mégalithe

♦Livre♦

Inca Quarrying and Stonecutting - Jean-Pierre Protzen

5. At Rumiqolqa, in contrast to Kachiqhata, the stones generally had been finished, or nearly finished, on five sides in the quarry. Once broken out of the quarry face, how were these stones hewn and dressed? Among the many blocks in the Llama Pit, one can observe blocks in ail stages of production, from raw, to roughly eut, to partially hewn, to finely dressed, so that one can easily imagine what the process may have been.

6. I have found enough tools at this site to be quite certain about the techniques involved in that process. These tools were simple river cobbles, used as hammer stones, loosely strewn about the chippings of andesite or halfway buried in them (fig. 13}. The map (fig. 15) indicates the location of each of the 68 lithic implements found in the Llama Pit.

These hammers were easily identified as they are foreign to the site because of both their shape and their petrological characteristics. Most hammers are of quartzo-f eldspathic sandstones, which have metamorphosed to various degrees, a few are of pure quartzite, others of granite, and some of olivine basalt. The weights range from a couple of hundred grams to hammers of 8 kg., with two groups in between, in the 2-3 kg. and the 4-5 kg. ranges. AU types of hammer stones have a hardness of at least 5.5 on Mohs' scale. This is comparable to the hardness of the andesite on which the hammers were used. The hammers are tougher than andesite, which, due to diffe rential cooling during its ...formation, is easily shattered by impact. The provenance of the hammer stones is most likely the nearby Vilcanota River.

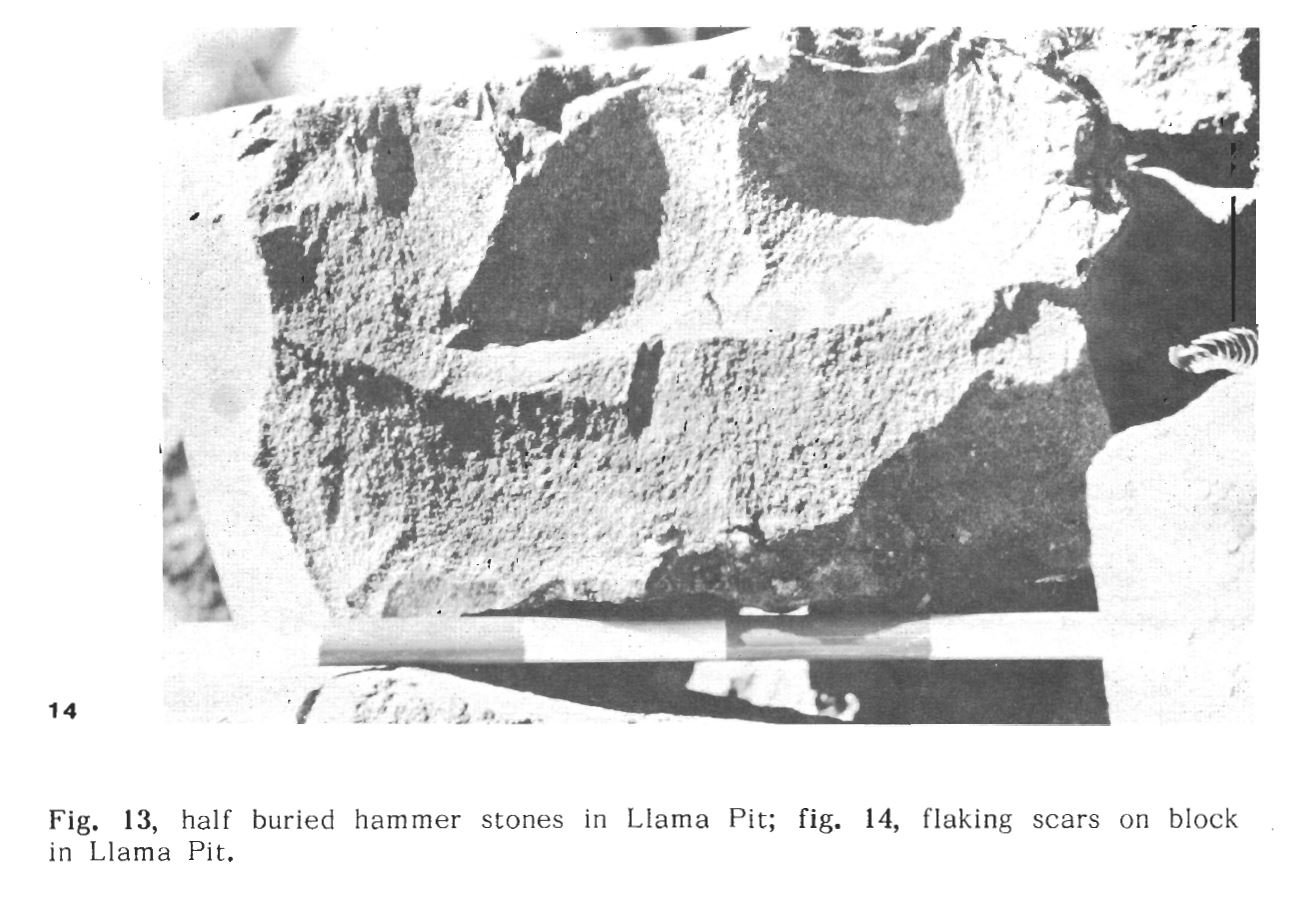

Once blocks were broken from the quarry face, the largest of the hammers were used to break them up and square them off by flaking. The fact that the technique used for shaping was one of

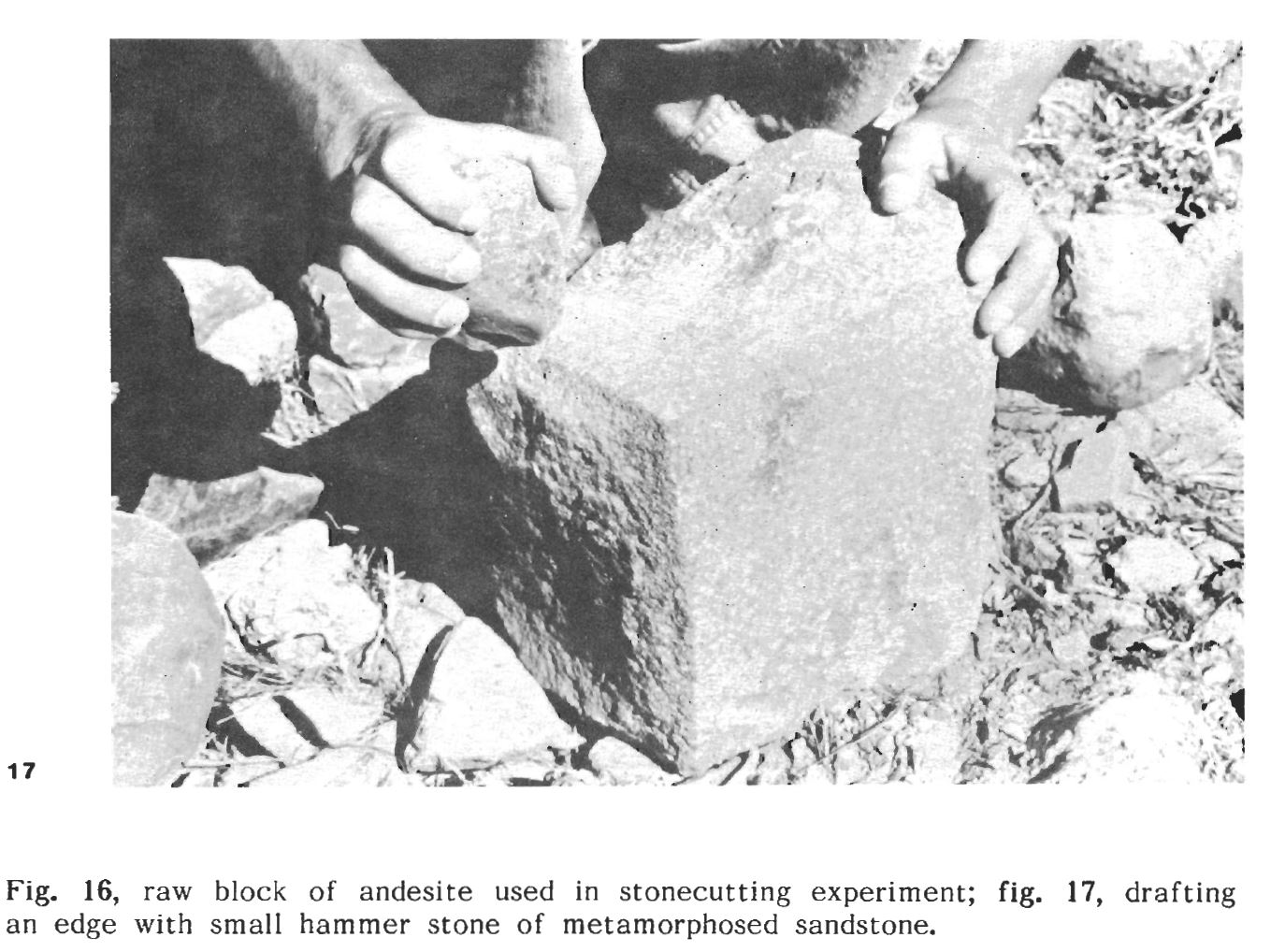

flaking is clear when one looks at the scars on actual blocks (fig. 14). The scars are similar to ones on flaked stone tools, but much larger. Dressing was done using medium weight hammers to eut the surfaces and smaller ones, of 200-600 gr. to draf t and finish the edges.

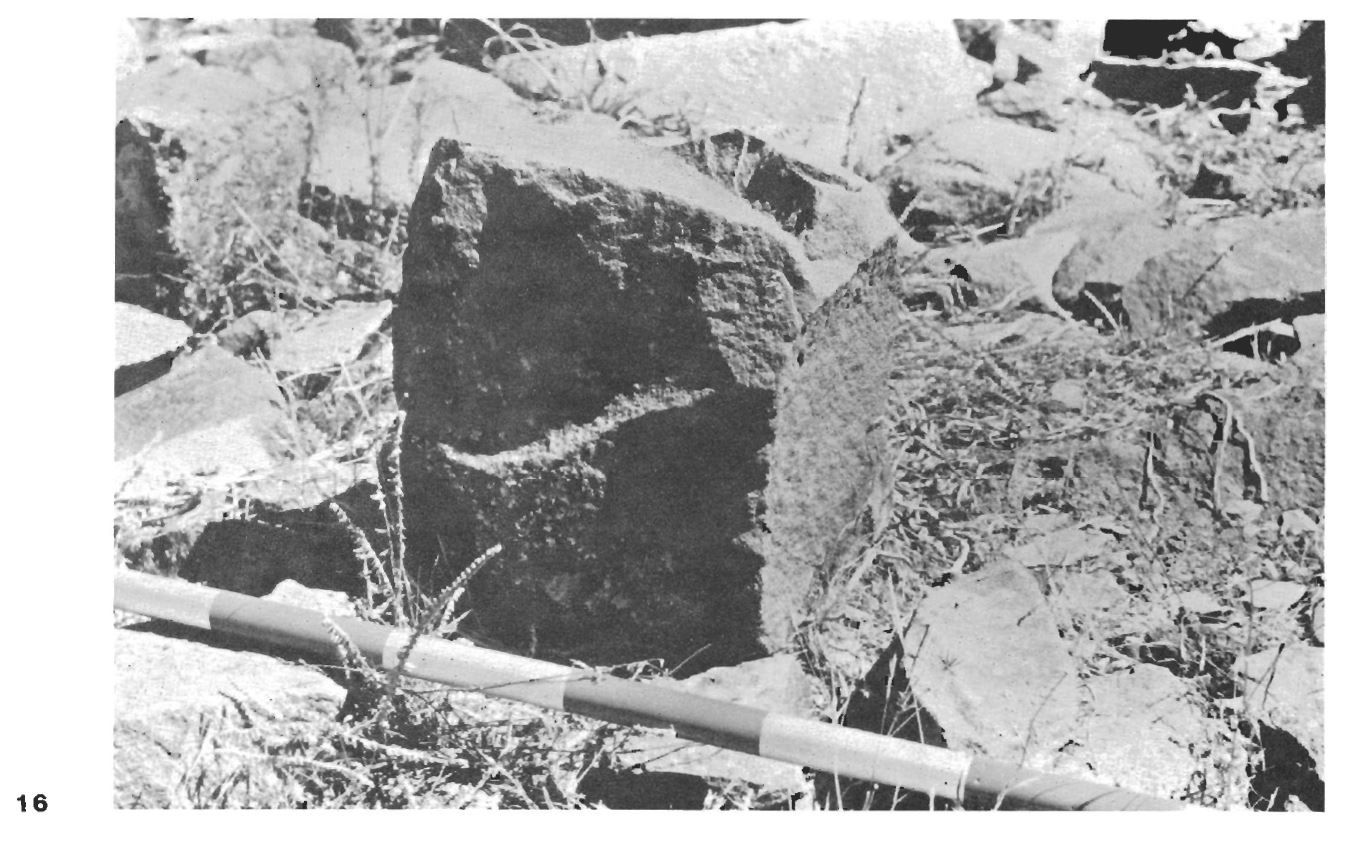

To test the above assertions, I have proceeded from observation to experiment. Starting wi th a raw block of andesi te, about 25 x 25 x 30 cm. (fig. 16), I first knocked off the largest protrusions using

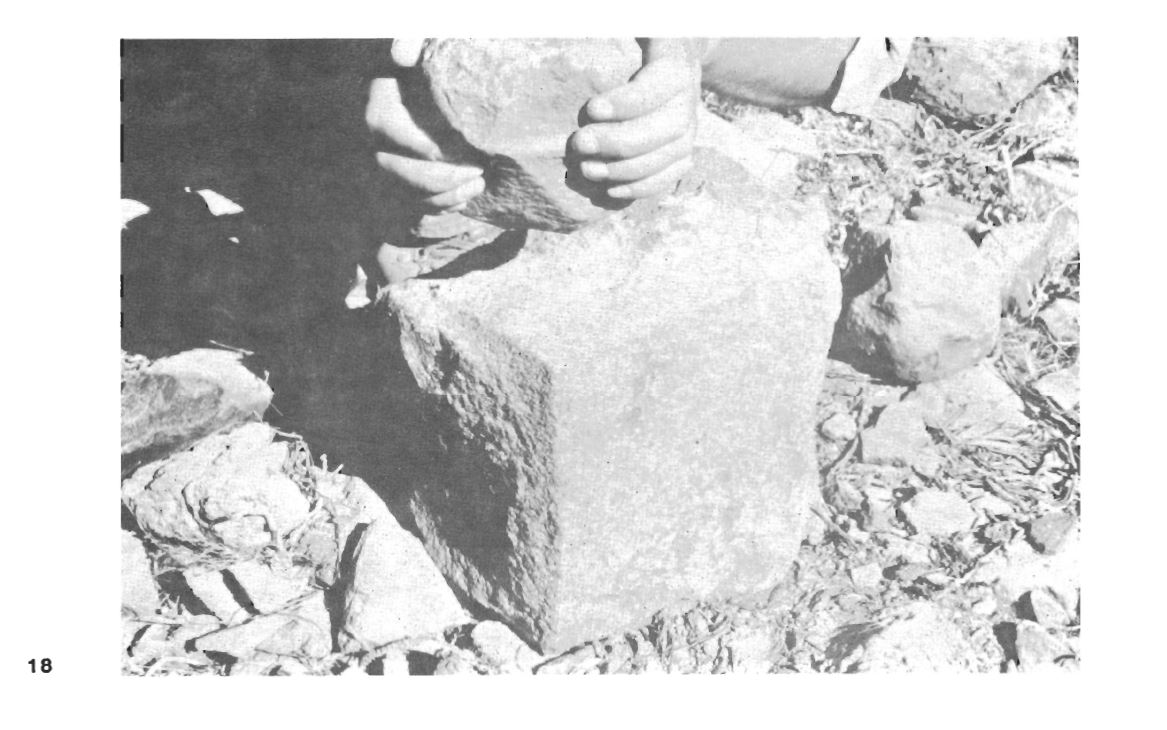

a hammer of metamorphosed sandstone of about 4 kg. to form a rough parallelipiped. Six blows were enough to complete this step. The next objective was to eut a face. Using another hammer of the same material and weight, I then started pounding at a face of the black, holding the hammer in my hands (fig. 18). Cutting stone in this fashion is essentially a process of crushing the rock.

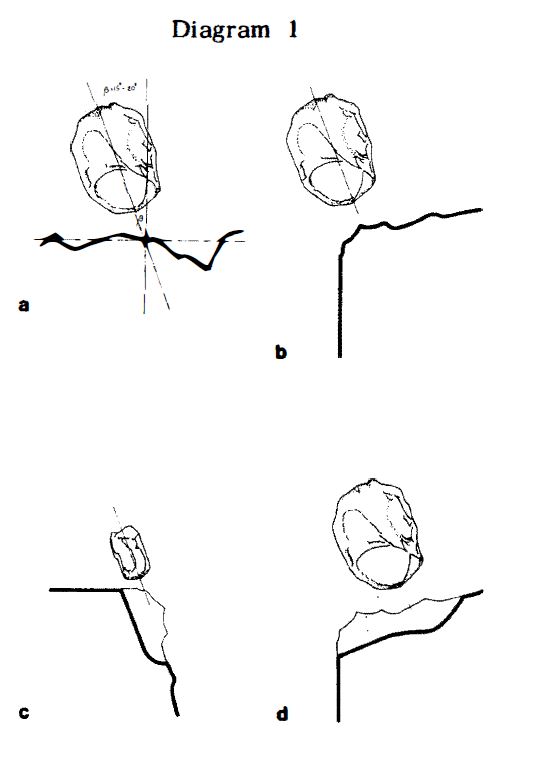

However, if one directs the hammer at an angle of between 15° and 25° off the normal to the surface to be worked, tiny flakes will chip off and the cutting is accelerated considerably (Diagram la). The efficiency of each strike is further enhanced by increasing the angle of impact to about 40-45° just before the hammer hits the surface. This is accomplished with a twist of the wrists at the last moment. The mechanics of this process are easilyexplained. When the hammer is directed vertically at the surface, the whole force of the strike is converted into compression, crushes the rock (or at worst may even split it}. As soon as the direction of the strike deviates from the vertical, the force of the strike is decomposed into a compression and a shear component. The larger the angle of impact, the larger the shear component becomes. It is the shear component of the force that tears off the small flakes.

7. After drafting the edges, I dressed two more faces, trying out a few more hammers between 3.5 and 4 kg. (fig. 18). Not all hammers used yielded the same results. One in particular was badly balanced, which made it bounce back at unpredictable angles and very difficult to contrai. Others did not bounce highenough to be used without effort. Nevertheless, dressing of three sides and the cutting of five edges took no longer than ninety minutes.

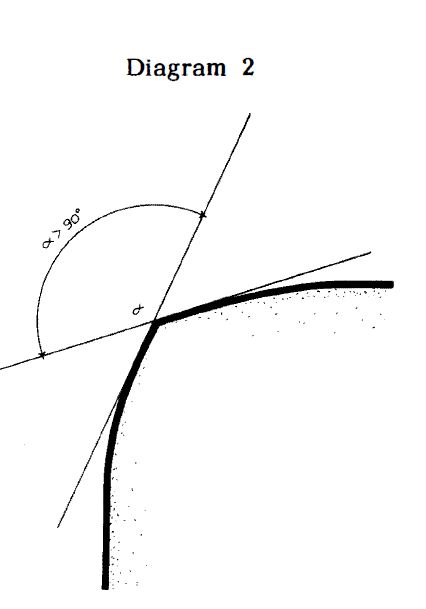

I had noticed that, on most blocks, the dihedral angles between two adjacent faces, measured at the edge, seemed to exceed 90° (Diagram 2). Verification on a group of 31 blocks yielded an average dihedral of 117° , with a range from exactly 90° to an extreme of 132° • This dihedral appears to be a direct consequence of the technique of drafting edges. The resulting protruding faces have the advantage of protecting the edges during transportation and handling. This technical detail of stone cutting accounts for the sunken joints that produce the chiaroscuro in Inca masonry.

8. The experiments show that stones can be mined, cut, and dressed with simple tools, yet with little effort and in a very short time. Is that the way the Inca stonemasons worked?

The physical evidence that they used techniques close to those developed in the experiment is abundant and ubiquitous. Pit scars similar to those obtained on the andesite block at Rumiqolqa are to be found on all walls, regardless of rock type (fig. 19). On limestone, the pit scars show a whitish discoloration of the stone. These white spots are the result of a partial metamorphosis of the limestone produced by the heat generated by the impact of the hammer stone (fig. 20). In each case, the pit marks towards the edge or joint are finer than in the middle of the face of the stone, suggesting the use of smaller hammers to work the edges.

The only doubt about the technique of pounding arises if I want to explain sharp concave edges, such as those observed in the steps at the "Throne of the Inca" at Saqsawaman (fig. 21). How would one pound out concave angles? At Rumiqolqa, I found a small, elongated tool, which dissipated my reservations. This tool, made of quartzite, could have been used as either a hammer or a chisel, as it shows wear on both the pointed and the blunt ends (fig. 22). The shape of the tool is such that it could also have served as a wedge.

At many Inca sites one finds eye-holes eut into stones: eye-bonders to tie down roofs, as at Machu Picchu; eye-holes of unknown use, as at the Inkawatana in Ollantaytambo and at the Qorikancha in Cuzco. Ali holes that I have investigated are pounded out. The holes show the characteristic pit marks and exhibit a conical shape on either side of the perforated stone. This suggests that the pounding was started from both sides and continued from both sides until the central portion of the stone was thin enough to be punched out. I know of only one eye-hole, in a stone in the courtyard of the Museo Arqueol6- gico in Cuzco, that could possibly support Bingham's suggestion that eye-holes were bored "probably by means of pieces of bamboo rapidly revolved between the palms of the hands, assisted by the liberal use of water and sand" (Bingham,

1930, p. 68).

9. Although there is no doubt that the technique of pounding was the predominant method of dressing stone, there is evidence in the area I have investigated that the Inca stonemasons had knowledge of other techniques to work stone. Many of the building blocks at Ollantaytambo exhibit highly polished edges, while the faces show the familiar pit mark. This polish may have been achieved with bars of pumice, of which I found a few fragments.

However, a few hundred meters from this stone, at the place known as Inkamisana, there is a number of genuine cuts forming a pattern of lozenges. These cuts result from abrasion, not from crushing or pounding. They may have been made with some kind of saw or file, but clearly not with a wire or string, as the cuts abut onto a vertical wall through which no wire could have been pulled. The cuts are, in fact, made of two smaller channels with a fine ridge between them that has been broken off (fig. 23). Similar cuts forming similar patterns can be found on stones labeled paving stones in the Archaeological Museum in Cuzco.

10. Wherever walls have been dismantled, one can clearly see the cuts made to receive the next course of blocks (fig. 27). Cuts like these are the manifest refutation of the often advanced hypothesis that neighboring stones have been ground against each other to achieve the perfect fit (Ravines, 1978, p. 559). Obviously, grinding would not have left marks like these. How then was the fit achieved?

Again, I tried to do it myself to get a better understanding of the technique involved. The experiment required two blocks of andesite, the one used in the dressing experiment and a larger one into which the bedding joint was to be cut. The face of the smaller stone shown in fig. 28 is the one for which the bedding joint was to be cut.

I started by putting down the face to be fitted onto the lower block and outlining its contours. Contemporary quarrymen dig up the root of a ubiquitous bush, named llawlli., which has a deep yellow sap, and use this root for marking in the manufacture of paving tiles. After outlining the ·bedding joint, I pounded it out. In the process a lot of dust is produced, which is quite useful, for when one puts back the upper black to check the fit, the dust compresses where the two faces of the joint touch, while it remains loose elsewhere. Where it is compressed is where one has to continue the pounding. Through repeated fitting and pounding, one can achieve a fit as close as one wishes. figs. 29 and 30 compare the fit I achieved in this fashion with an actual fit in the Inca wall of the Amarukancha in Cuzco.

11. The technique for fitting lateral joints I assume to be similar to that used

for the bedding joints:

The new block to be laid is fitted into, and the joint cut out of,

the lateral block or blocks already in place.

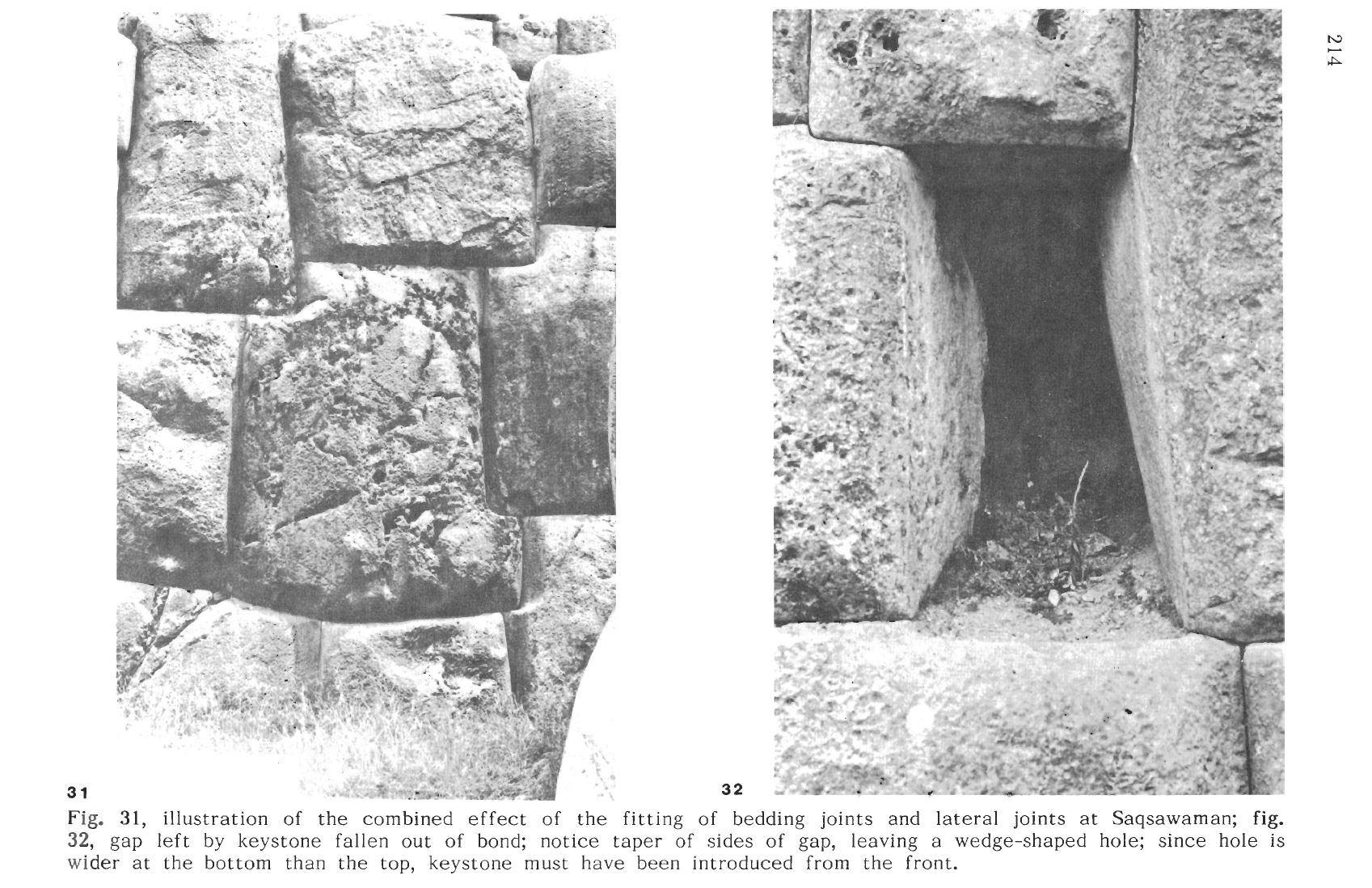

The combined effect of the fitting of bedding joints and lateral ones is neatly

illustrated at Saqsawaman (fig. 31), and it takes some of the magic out of the

famous "twelve angle stone" in the retaining wall of Inka Roka's palace.

12. Laying sequences

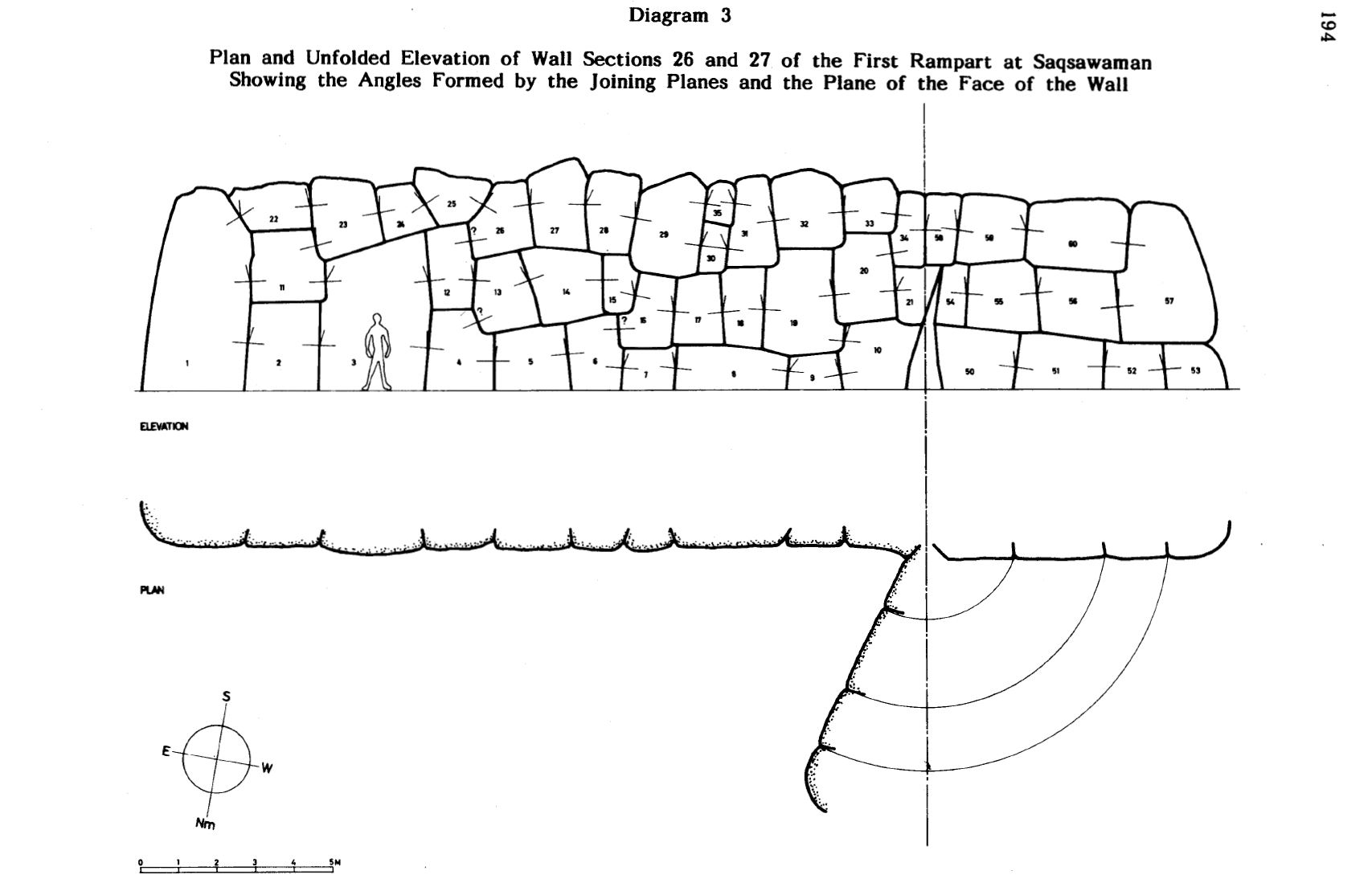

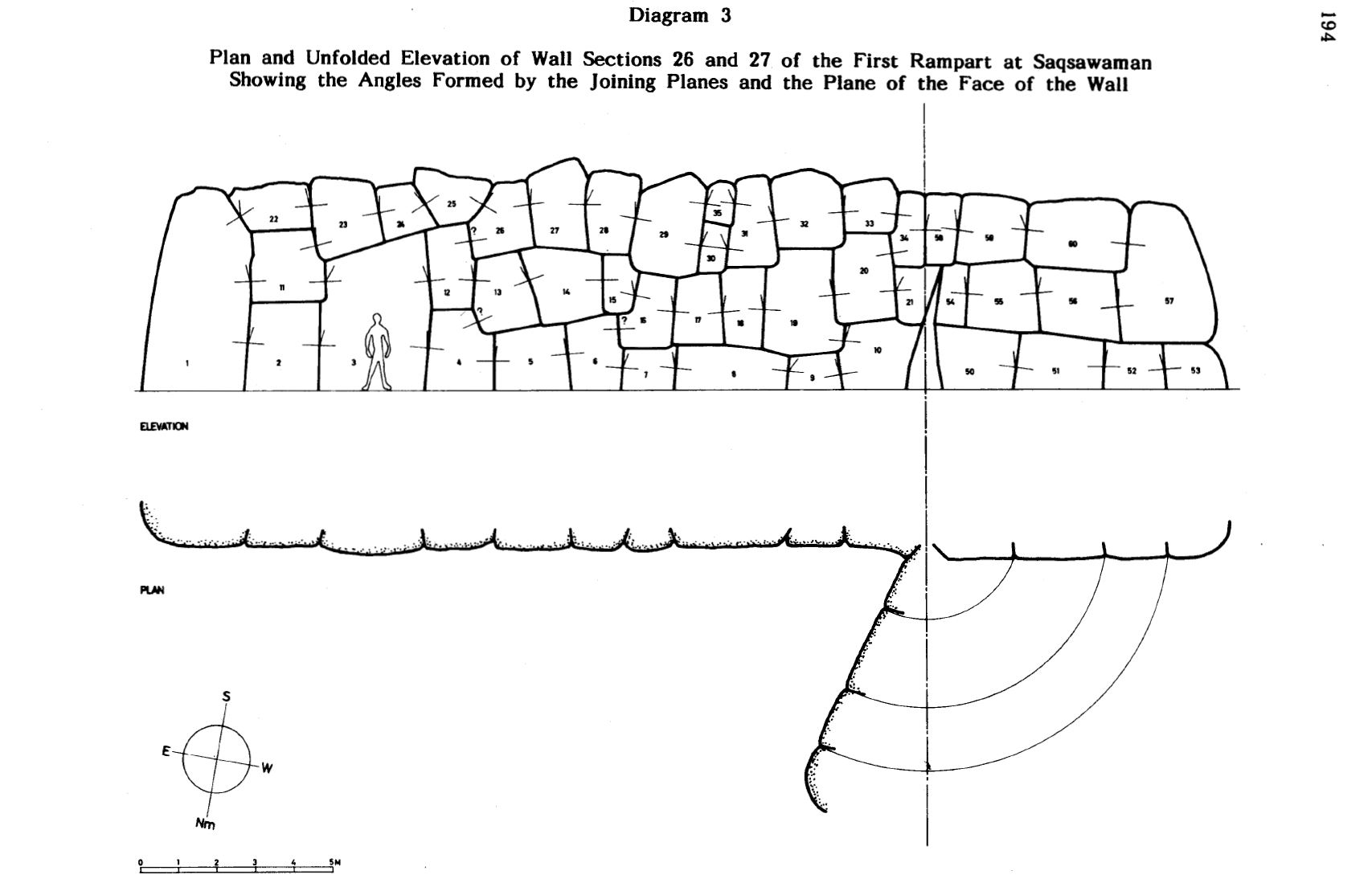

The matter of lateral fitting raises some questions about the sequence in which the blocks were laid. The sequence may not matter so much for masonry with a regular bond, but it certainly becomes critical in masonry with an irregular bond. To investigate laying sequences, I have surveyed one of the fortification walls at Saqsawaman. The unfolded view of walls 26 and 27 of the first rampart shows the orientation and magnitude of the angles formed by the joining planes and the plane of the face of the wall (Diagram 3).

13. That some keystones were introduced from the front is manifest in a gap found in the second rampart at Saqsawaman (fig. 32). The tapering sides of the gap indicate that it was a keystone that had fallen out of the bond. Since the width at the bottom of the gap is broader than at the top, the keystone must have been introduced from the front. If, as I suspect, the Incas used earthen embankments to raise the building blacks into position, then it would make sense to assume that keystones were always inserted from the front. Each of the courses in these walls proves to have a block that can reasonably be regarded as such a keystone: blacks 15, 58, 30, and 35, and possibly 28 and 25. The course formed by blacks 20 and 57 does not have a keystone because it does not need one. Block 57 is a corner stone which could easily be put in place last. Corner stone 1 was most likely erected after blacks 2 and 11 were in place.

13. These conclusions about laying sequences are not meant to be definitive for a number of reasons. First, more walls need to be analyzed for sequence; one wall is simply not enough of a sample. Second, because of the fit, which does not allow one to introduce even a knife blade into the joints, I have not been able to measure all the internal angles and in particular those of the bedding joints. Where I have succeeded in making such measurements, I often could do so only to a depth of about 5 cm. This depth is not sufficient, as the joining planes quite frequently are not fiat but warped, with the result that farther in the direction of the joining plane might be different from what I have measured on the surface. Third, and most importantly, firm conclusions about the laying sequences can only be reached after careful motion studies have been conducted.